Daniela Rywiková

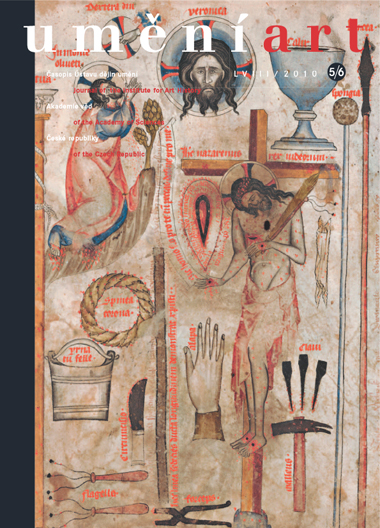

"V chlebnej tváři ty sě skrýváš…" Obraz Veraikonu v kontextu eucharistické zbožnosti pozdně středověkých Čech

The image of Christ's holy face was one of the most revered icons throughout the Middle Ages, both in Byzantium and in the West. Reverence for the Vera Icon derived from the belief that the image was not made by hand but was rather the authentic imprint of Christ's face - acheiropoietoi. The Vera Icon was thus de facto the 'material' manifestation of God in this world and at the same time represented an effective medium of communication between the faithful and God. Like the consecrated host, it 'contained' the physical substance of Christ. The Vera Icon begins to appear in Bohemian art of the Middle Ages from the start of the 14th century and it was initially linked to the monastic environment. Around the middle of the 14th century the image started to figure in church decorations, where it is not unusual to find it in the vicinity of the sanctuary, as though in confirmation of the authenticity of the Body of Christ therein. The frequent depiction of the Vera Icon in images of the St Gregory Mass, on the altar, or as part of Arma Christi usually depict Christ's face not on a painting set on the altar table, but on a sudarium - a cloth showing the face of Christ, which is a part of divine reality and divine intervention, akin to Christ's physical presence on the altar and the miracle of transubstantiation. This is how, for instance, the Vera Icon in the passionale of Abbess Kunigunde or on the reverse of paintings of the Madonna and Child must be understood, where the sudarium alludes to the veil of the bride of Christ. The Vera Icon also played a role in the restoration of royal power in Bohemia by the Emperor Sigismund in 1436. Alongside its devotional significance it was also intended to confirm Sigismund's entitlement to the Bohemian throne, and in this context it was perceived similarly by both official religions in Bohemia: as signifying the presence of God and confirming the 'veracity' of both the political and theological argument.

Full-text in the Digital Library of the Czech Academy of Sciences:

https://kramerius.lib.cas.cz/uuid/uuid:24b14445-2910-cc96-a4bb-9e769281ff98

< back