Klára Benešovská

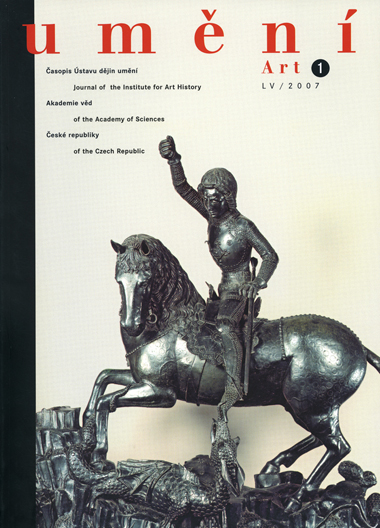

St George the Dragon-slayer - the Eternal Pilgrim without a Home?

The article suggests some new ways of understanding the 'place' of the St George sculpture in the court art of the second half of the 14th century, inspired primarily by the Italian milieu. The composition of the sculpture, the type of the saint's armour and hairstyle, and, among other things, the fauna that decorates the pedestal all reveal the Italian influence.

In the introduction, the author summarises the conclusions of the older Hungarian and German research on the work, documented in the sources, of the metalworkers Martin and George of Klausenburg (Kolozsvár, Cluj) in Great Oradea (Nagyvárad), in connection with the Prague St George sculpture. (The author regards the monumental equestrian statue of St Ladislaus there, commissioned by the bishop in 1390, as a possible response to the famous bronze Regisole monument, returned in 1335 after twenty years from Milan to Pavia ['secunda Roma'], where it embodied the independence of the town.) The author recalls Viktor Kotrba's (1969) publication treating the major restoration of the sculpture by Julius Schneider from Munich in 1941-1942. She also draws attention to the contribution made by Ernő Marosi in his recent works on the subject of the Prague sculpture (1995, 1999). Likewise, she recalls a half-forgotten chapter of Czech research on the development of the cult of St George under Charles IV, documented by the relic 'vexillum sancti Georgii' in the St Vitus treasure in 1355 and the 'caput draconis' at Karlštejn (Olga Pujmanová, 1980 and Barbara Drake Boehm, 2006). In the future, given the fact that the sculpture may have been imported, it will be necessary to return to this subject in a more detailed study of the diplomatic contacts between the Luxembourg and Anjou courts during the negotiations of the marriage of Charles' son Sigismund to Maria, heir to the Hungarian Kingdom, and later under Sigismund's rule.

The sculpture cannot be classified as an equestrian monument. It depicts the culminating moment of the St George legend of Jacobus de Voragine, when the saint on horseback strikes the dragon to the ground with his lance, so that the princess can then lead it off, attached to her belt, to the liberated city. The composition is defined by the main vertical axis, represented by the (lost) lance, around which the horse, rider and dragon turn. Among medieval monuments, it is the only surviving execution of this motif in a large, three-dimensional bronze work. The motif, with its dynamic, revolving composition, is frequently found in paintings and reliefs. The unusually precise, realistic rendition of the anatomy of the horse and the lizards and grass-snakes depicted on the pedestal (this type of snake [Pseudopus apodus] was only to be found in the South of Balkans) and the attention to detail in the treatment of the armour and saddle, indicated a heightened interest in the real world of nature and objects and in the use of casts (see Cennino Cennini, the Carrara court in Padua in the 14th century). In these respects, the sculpture resembles court works of art in gold. The sculpture was also probably made at one of the courts, which fostered the cult of St George. In addition to the Anjou court, the author mentions examples from the Visconti court. Aside from reliefs and small statues, she draws attention to the closest analogy to the Prague sculpture: the illusive painting of a St George sculpture on a bracket, executed by Giovannino di Grassi on the jamb of the northern sacristy in the Milan cathedral in 1395. On that occasion, Giangaleazzo was elevated to a dukedom by Václav IV, King of Bohemia and of the Romans (or rather, by his plenipotentiary Beneš of Choustník).

Even if, in the future, the court at which the Prague sculpture was made is identified, along with the person who commissioned it and the person who designed the model (including confirmation of the role of the brothers of Cluj) and even if the journey of the sculpture to Prague is reconstructed, the work will remain a testimony to the inspiring influence of the northern Italian milieu.

Full-text in the Digital Library of the Czech Academy of Sciences:

https://kramerius.lib.cas.cz/uuid/uuid:6dfd2e55-1f12-41e4-9e2d-bdd385049637

< back